We all know physical activity is key in achieving our health and fitness goals, but how much is enough? What are the daily recommendations to realize the benefits of physical activity? Read ahead for the importance of physical activity and national recommendations from American College of Sports Medicine, Centers for Disease Control, American Heart Association, and the Federal Guidelines!

One of the biggest struggles I hear from people wanting to begin an exercise regime is the “all or nothing” mentality. They don’t think they can be like the fitness superstars they see online and on TV, or believe they could ever look like those athletes or obtain the same health benefits as they do, so why even bother?

The truth is, a little can go a long ways in physical activity. I wanted to write a post sharing the importance of physical activity, including what qualifies as physical activity, the health benefits that can be gained, and how these benefits can be achieved. The more I looked at the material, though, the more I realized it would be a bit much for one post, so I’ve split it into a two part series. This week’s will cover what physical activity is and just how much you should be doing to see those health benefits. Check back next week for the various health benefits you can expect to see just by increasing your physical activity!

Be sure to always consult with your physician before starting a new fitness program if you have any health concerns or questions! While the benefits of physical activity far outweigh the risks, it’s always better to be safe than sorry.

Let’s get started!

This first part of the series will deal with just getting moving!

First off, we should define just what physical activity is. Physical Activity is any bodily movement produced by the contraction of skeletal muscles and requires increased calorie intake. This can be anything from walking around the neighborhood, mowing the lawn, or even doing chores. Exercise is physical activity with the specific intent to maintain or improve physical fitness. Now we’re moving more into focused, structured movement, like going for a run or completing a strength training circuit. Physical Fitness, then, is our ability to carry out daily activities with vigor and without fatigue. Basically, can you do what you need to do on a daily basis to live independently?

There are two components to be considered under physical fitness: Skill Related and Health Related. Aptly named, skill related components consist of speed, agility, coordination, balance, and power, while health related components refer to cardiovascular [the efficiency of your heart and supporting vessels to perform under stress], endurance, body composition, muscle strength, and flexibility. This series will mainly focus on the health related components of physical fitness when we go over the benefits of physical activity.

So why is physical activity such a big deal? The simplest concept for it is the Dose-Response Relationship. The dose-response relationship is a relationship in which a change in the amount, intensity, or duration of exposure is associated with a change in risk of a specified outcome. If physical activity is our exposure and chronic disease is our outcome, then higher physical activity corresponds with lower risk for chronic disease. In simpler terms, more of a good thing equals more of a good outcome and less risk for bad outcomes.

Professor Jerry Morris was the first to demonstrate this connection in the 1950’s by comparing the health of bus conductors vs the health of the drivers. The conductors, who were on their feet and moving considerably more than the drivers, showed decreased risk for chronic disease. These were among his first findings that linked exercise and health.

Physical activity and physical fitness effect everyone’s health, but how much is enough? The recommendations for physical activity are constantly changing as new information is learned. We’ll take a look back at the three more recent recommended guidelines and wrap-up with the expected benefits realized from following the minimum of these guidelines before going more in depth into the benefits next time!

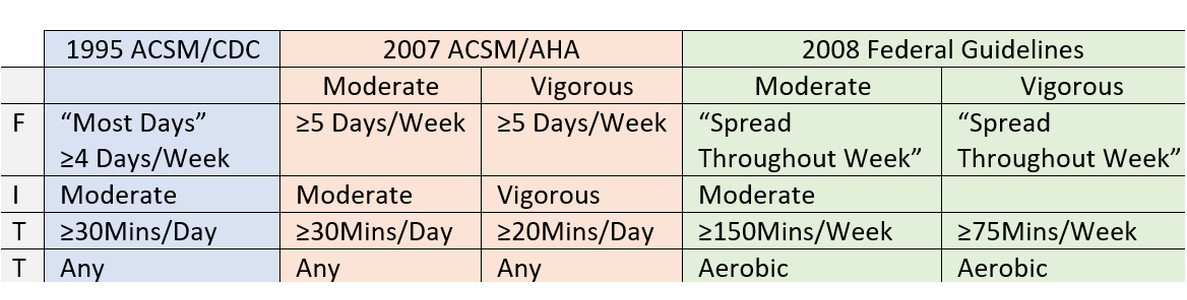

When discussing a physical activity program, there are 4 domains we can use to describe it, conveniently put together in the acronym FITT: Frequency [how many days a week], Intensity [difficulty], Time [duration], and Type [mode of activity]. See if you can identify these 4 domains of each set of recommendations and then check the table below to see how you did!

When talking about intensity, these guidelines refer to the term METS [metabolic equivalent]. If you currently use METS to track your workouts, note that here, moderate intensity is 3-5.9 METS and vigorous intensity is any activity above 6 METS. If you’ve never heard of METS before, that’s OK! All you need to know is that they’re a way to gauge how hard you’re working, the larger the number, the harder you’re working.

Physical Activity Recommendations

Our first set of physical activity recommendations was released in the ’90s. In 1995, the American College of Sports Medicine released a set of guidelines with the Centers for Disease Control. These guidelines stated that a healthy adult should accumulate at least 30 minutes of moderate physical activity in at least 8-10 minute bouts most days of the week.

Then, in 2007, the American College of Sports Medicine released an updated set of guidelines with the American Heart Association. These determined that a healthy adult should accumulate at least 30 minutes of moderate physical activity in at least 10 minute bouts at least 5 days a week, or 20 minutes of vigorous activity 3 days a week.

Physical activity here is any appropriate recreational, lifestyle, or activities of daily living. This could be hiking, jogging, kayaking, walking the dog, mowing the lawn; anything that gets you up and moving! Also note that both of these sets include that “in 10 minute bouts.” Your physical activity doesn’t have to be all at once, you can break it up into chunks, doing 3 bouts of 10 minutes. Every little bit makes a difference!

More recently, the 2008 Federal Guidelines state that healthy adults should accumulate at least 150 minutes a week of moderate intensity, or 75 minutes of vigorous intensity aerobic activity, in bouts greater than 10 minutes and preferably spread throughout the week. Here, we also see that dose-response relationship, meaning an increase in volume will increase our benefits. For additional health benefits, it is recommended to complete 300 minutes/week of moderate intensity or 150 minutes/week of vigorous activity. This is also the first set to include a recommendation of strength training 2 days/week. Note that this set specifies aerobic activity, so we’re moving more into structured, prolonged activities.

See the comparison image below to see these guidelines broken down into their domains!

Benefits from these Guidelines

We’ll discuss the various health benefits that come with increased physical activity more in Part II, but for now, lets take a look at what we can expect to see with the completion of the minimum physical guidelines from the 2007 ACSM/AHA and 2008 Federal guidelines. Sedentary adults starting from the couch and beginning a new fitness program that satisfies these recommendations can expect to see improved physical fitness and a significant decrease in their risk of chronic disease, such as heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and obesity. Already moderately physically active adults can also expect to see a decrease in chronic disease by continuing to meet these standards. However, highly active adults who follow these guidelines can actually see a decrease in their physical fitness and an increase in their risk of chronic disease because these guidelines are lower than their regular physical activity. So if you’re already training above these minimal recommendations, keep it up! And if you’re just starting out, these recommendations will set you on the path to a healthier, happier you!

What’s the Inverse of This?

Following the dose-response relationship, we know the more we move, the more benefits we can expect to see. But what about going the other direction? According to the CDC, in 2015, 50% of adults aged 18 years or older did not meet recommendations for aerobic physical activity. Studies have shown that inactivity is linked to higher rates of all-cause mortality [death]. The highest probability for survival was for those who reported sitting the least. Sitting for long periods of time can influence our risks for all-cause mortality, as well as our functionality. Our muscles atrophy and become weak, our joints become stiff, and functional capabilities become severely limited with prolonged inactivity. Even if all you start with is standing up wile you work, or taking 15 minutes to walk around the block, it makes a big difference!

What About Steps?

With the Fitbit/fitness tracker craze of recent years, I wanted to include a bit about step recommendations. It’s become very common for people to record their daily step count as a training metric, but what is considered a healthy amount of steps for one day?

Nearly every fitness tracker now comes pre-programmed with the daily goal of 10,000 steps. It has become the accepted norm that if you want to accomplish your activity goals for the day, this is the number you need to achieve. But where did this number come from?

The 10,000 step/day rule has no scientific backing, and is not magical in any way. A CEO was trying to market his fitness tracking product and needed a clean, whole number to promote it’s capabilities. 10,000 was that round number that appealed to consumers. The idea took hold and is now considered the holy grail of healthy steps.

According to the American College of Sports Medicine, healthy adults should accumulate at least 7,000 steps/day to maintain functionality. To maintain body weight and reap health benefits, men should achieve at least 11,000-12,000 steps/day and women should achieve 8,000-12,000 steps/day. There is also a recommended step rate for those utilizing this metric. If you have a piezoelectric pedometer, it will be able to measure your step rate per minute. ACSM recommends a step rate of 100 steps/minute.

I know a lot of this must seem like common sense, but the main take-away is this: move more! Physical activity is such an important factor in our health, yet I think many of us take it for granted. It keeps our muscles and bones in good health and maintains our range of motion and functional capabilities. More importantly, it helps us stay healthy and avoid all-cause mortality. Some of the most common, chronic health problems in our society today, such as heart disease, type II diabetes, obesity, and stroke, are preventable just by living an active lifestyle and eating right. And you don’t have to train for five hours a day to benefit from physical activity. Every little bit helps! Go for a walk, take the stairs, park at the back of the parking lot, ride your bike; anything that gets you up and moving. Always remember, an inch of movement will bring you closer to your goals than a mile of intentions!

Some helpful links:

Check out more about Jim Morris and his studies linking exercise and health!

Read up on the more common chronic diseases and their causes from the CDC!

Learn more about tracking METs and see what your current activities are measured as!

These recommendations are geared towards adults, check out more about recommendations for children and different activities that count!